To know more about Les 3 sex*'s editorial policy and texts selection, click here.

☛ Cette chronique est aussi disponible en français [➦].

Translated by Chloé Sautter Léger

In 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a statement condemning female genital mutilation (FGM) (WHO, 2018). However, still today, the WHO estimates that 200 million women live with the wounds of these procedures (WHO, 2018). Why is it that these practices, which many countries have condemned as a violation of human rights committed against women and children (Kaplan et al., 2011), continue to be so widespread? This text will firstly define the concept of female genital mutilation, and then discuss the social beliefs in which these practices are based. It will conclude with an analysis of their biological and psychological impacts.

What is female genital mutilation?

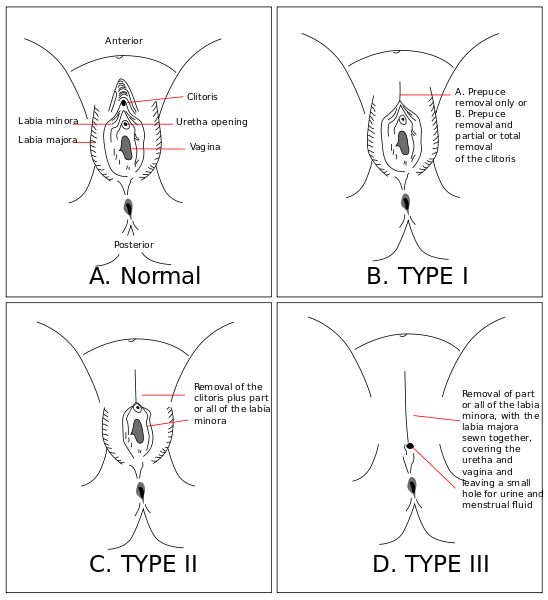

Female genital mutilation is defined as any type of surgical intervention which intentionally alters or wounds women’s external genital organs for non-medical reasons (WHO, 2018). Possible reasons include “improving” the external aspect of the organs, guaranteeing women’s virginity, or conforming to social norms. FGM are usually performed on children or adolescents, and sometimes on adult women. The WHO classifies them into four categories (2018).

Type I mutilations, known as “clitoridectomies,” correspond to a partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or of the prepuce. The ablation of the hood of the clitoris (prepuce) renders it so sensitive that it may become painful. Type II, also referred to as “excision,” represents any kind of ablation of the labia minora, with or without the removal of the clitoris and of the labia majora. Type III, “infibulation,” is the narrowing and sealing of the vaginal opening, by ablating and stitching together the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without the removal of the clitoris. Type IV refers to any other type of intervention on female genitalia, for example piercings, incisions, cauterization (WHO, 2018). Type IV interventions may be matters of personal choice. Burns, usage of caustic substances, or stretching of the labia minora also can be grouped under this last category (Jaeger et al., 2009). Although practices vary among countries and traditions, Type II procedures are believed to be the most common, representing 80% of reported mutilations (Berg et al., 2010). Most of the time, operations are performed without anesthesia or antibiotics, and in non-sterile conditions (Iavazzo et al., 2013). Tools used to perform the surgeries include razor blades, broken glass, knives, and scissors (Berg et al., 2010). In some countries mutilations are performed on girls ages 4 to 8, and sometimes only a few days after birth (Jaeger et al., 2009).

In many cases, FGM have important consequences on young girls in the period shortly following the operation. Both because of the nature of the procedure and because of the poor sanitary conditions the operation is often performed in, girls are prone to suffer from prolonged bleeding, local or generalized infections like Hepatitis B or HIV, and to experience sharp pain (Jaeger et al., 2009). Many also suffer psychological consequences directly after the operation, such as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) (Kaplan et al., 2011). In the long term, consequences include infertility, genital infections, childbirth complications and abdominal pain (Kaplan et al., 2011).

FGM are practiced widely in African, Middle Eastern and South-West Asian countries (Andro and Lesclingand, 2016). Since the practice is considered illegal and is often performed outside of hospitals, it is hard to obtain accurate data about its prevalence. Some countries, nonetheless, have censuses that enable a quantification of the phenomenon. In Egypt for example, a 2014 survey shows that 92% of women aged 15 to 49 have undergone a genital mutilation (Ministry of Health and Population of Egypt, 2015). Mutilations are not necessarily as widespread in other countries—Nigeria, for example, had a mutilation rate of 20% for women aged between 15 and 49 in 2003 (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004).

Why practice FGM?

Many different kinds of social beliefs and customs motivate FGM practices around the world. The most often cited reason for a woman to undergo altering of her genitalia is the preference of her future husband (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004). In communities where these operations are a standard, genital mutilation is a prerequisite for marriage and serves as a guarantor for social security (Jaeger et al., 2009). In a similar vein, FGM are sometimes rites or traditions. Parents are pressurized to subject their daughters to such an operation, which they do partly to avoid social exclusion (Jaeger et al., 2009). They may also perpetuate the practices to maintain family honour (Berg et al., 2010). In some cases, the practice is also an act of resistance to Western culture, seen as lacking in morality (Jaeger et al., 2009). A second widely cited reason for female genital mutilation is controlling women’s sexuality (Berg and Underland, 2013). In fact, mutilations serve to assure women’s virginity until they marry and limit their sexual pleasure so that they may not be tempted to cheat on their future husband (Jaeger et al., 2009). Other beliefs cultivating these practices involve aesthetic conceptions of female beauty or assumptions about bodily hygiene (Jaeger et al., 2009).

How do FGM affect women’s sexuality?

Once they begin to be sexually active, women who underwent genital mutilations may feel pain and discomfort which can affect sexual satisfaction (Berg et al., 2010). Firstly, with cases of clitoridectomy or excision, pain can result from the friction with the scarring of the wound during penetration. There is also a possibility that scars tear open, causing a tremendous amount of pain (Berg and Denison, 2012). In 1992, Van Der Kwaak reported that in certain cases, the partner uses a knife or other tool to open the access to the vagina for the first penetration. Mutilations that remove the clitoris overtly injure the clitoral nerves (Berg and Denison, 2012). As a result, the region of the clitoridectomy becomes less receptive to tactile stimulation, and sexual pleasure becomes harder to experience (Berg and Denison, 2012).

Research has shown, however, that women who have undergone genital mutilations develop a capability to compensate for the damaged regions through increased sensibility and erotism of other regions of their body (Berg and Denison, 2012).

For example, breasts can become more erogenous on women whose genitals are less sensitive (WHO, 2000). Many genitally mutilated women report what seems like symptoms of sexual dysfunctions, like disorders related to sexual desire, to orgasm, or to sexual excitement, along with sexual pains which create significant personal distress (Alsibiani and Rouzi, 2010). However, health and sexual problems do not affect 100% of women after a genital mutilation (WHO, 2000).

Besides, since sexual satisfaction is subjective and hard to evaluate, researchers do not agree on the impacts of FGM in this regard.

An article published in a journal demonstrated that researchers’ methodologies in investigating the physical and sexual consequences of FGM are often defective, and that a clear difference has not been proven between sexual desires of women who have been mutilated and those who have not (Makhlouf Obermeyer, 2005).

Four studies conducted between 2000 and 2005 at the Research Center for Preventing and Curing Complications of FGM in Florence also attempted to measure psychological impacts of genital mutilation on sexual satisfaction (Catania et al., 2007). Over 250 women from different backgrounds evaluated their sexual behaviour through interviews and surveys. The conclusion was that regardless of the type of genital mutilation undergone, women are capable of reaching orgasm (Catania et al., 2007). Most of the women reported reaching it through vaginal penetration, while a smaller percentage of them required manual stimulation (Catania et al., 2007). About 90% of the women questioned reported that intercourse brought them pleasure (Catania et al., 2007). These studies, however, disregarded results of women who had suffered severe repercussions from the operation, such as genital or urinary tract infections. This conclusion therefore possibly does not adequately reflect the reality of all mutilated women.

What are the psychological impacts of FGM?

Anatomical abnormalities may have the most obvious impact on genitally mutilated women, but psychological consequences also play a major role on their experiences. It has indeed been shown that mutilations do not in themselves have an impact on sexual desires; whereas psychological conditioning does have an impact (Berg and Denison, 2012).

Negative past experiences and pain associated with penetration could bring women to avoid sexual activity or to perform dissociation—to separate themselves temporarily from reality during intercourse (Berg and Denison, 2012).

Psychological consequences linked to female genital mutilations affect other parts of women’s lives as well. Firstly, the mutilation operation itself, which is often performed at a very young age, is usually traumatic (WHO, 2000). The memory of it persists vividly and intensely even years later, and can remain associated with the actions of crying, pain, and humiliation (Berg et al., 2010). These emotions are first felt during childhood and are experienced again at a moment in women’s lives where they have to form an opinion of themselves and develop their self-esteem (WHO, 2000). The genital mutilation is hence associated with chronic mental disorders long after the event (Vloeberghs et al., 2012). In fact, once they reach adulthood, genitally mutilated women are more likely to be diagnosed with psychological conditions, to suffer from anxiety, depression, or phobias (Berg et al., 2010; WHO, 2000; Vloeberghs et al., 2012). They also have lower self-esteem than other women (Berg et al., 2010).

Repair surgeries?

When they reach adulthood, some women attempt to counteract the anatomical consequences of genital mutilations through reparatory surgery. Since the 1990s, methods adapted to the different types of mutilations were developed, in order to help the women living with negative repercussions to recover a satisfactory sexuality (Andro and Lesclingand, 2016). The first method, defibulation, is the inverse of infibulation and unseals the scar tissue attaching the labia majora to each other, freeing the vaginal and the uterine opening and the clitoris (Collinet et al., 2004). It is a simple surgery, which can be performed at any moment of a woman’s life (Andro and Lesclingand, 2016). The clitoridic surgery, which reconstructs the clitoris following ablation, is more complex. The procedure consists in surgically recovering an internal section of the clitoridic gland and repositioning it where the clitoris was originally placed (Ouédraogo et al., 2013). A study that surveyed women who underwent this reconstructive operation has shown that most women were satisfied with the result, and remarked that it improved their quality of life and their sexuality (Ouédraogo et al., 2013).

What other ways are there of surmounting the consequences of FGM?

Reconstructive surgery is not always available or feasible for all women affected by FGM. These surgeries also do not tackle the psychological repercussions. To help women improve satisfaction of their sexual life, psychological, sexual, or relationship guidance has been developed (Beltran et al., 2015). In fact, in some cases, sexual dissatisfaction was caused not by the physical constraints related to the mutilations, but rather by trauma from the operation, intrusive thoughts, or related shame. In such cases, psychological therapy can help alleviate some aftereffects and sexual problems (Antonetti et al., 2015).

A Note on Gender Identity

The debate over FGM cannot be addressed without touching upon the issue of sexual identities. In communities where mutilations prevail, the operation is often seen as a rite of passage in the process of becoming a woman (Van Der Kwaak, 1992). These practices can be evaluated positively, as women who are mutilated correspond to a social norm (Schweder, 2000). In many countries, women with mutilated genitalia are believed to have more beautiful, more “female,” and more honourable bodies (Schweder, 2000). In some cultures, the clitoris and/or the labia minora are perceived as repelling to sight and touch (Schweder, 2000). Mutilating organs would, in this perspective, be a way of rendering the body more attractive. Furthermore, in some cultures, the clitoris is seen as a “masculine” organ, since it becomes erect with sexual arousal (Schweder, 2000; Can Der Kwaak, 1992). By removing the clitoris, a woman may attain a totally “feminine” identity and appreciate the idea of not bearing a non-desired “male” organ (Schweder, 2000). Not to mention that from the male perspective, leaving “male” organs on women could interfere with their power and authority (Fainzang, 1985). A woman keeping her clitoris—the counterpart of the penis, the organ of power—could fail to adopt the submissive behaviour expected of her (Fainzang, 1985).

The question of female genital mutilations is, to this day, a highly controversial topic. Since the practices are often directly linked to traditional beliefs and practices, adopting a judgmental approach from an outsider’s perspective is not unproblematic. What’s more, even within the scientific community, female sexuality is still far from being well understood and a matter of consensus. Even if negative psychological consequences seem to occur from FGM, these practices have an important place in the cultures in which they occur. In any case, an in-depth and critical questioning is needed, to determine how to approach and help women who have experienced mutilations or who are at risk of experiencing them in the future.

To cite this article:

Delage, É. (2018, May 24). Clitoris, Orgasm, and Identity: Female Genital Mutilations. Les 3 sex*. https://les3sex.com/en/news/3/clitoris-orgasm-and-identity-female-genital-mutilations

Comments