To know more about Les 3 sex*'s editorial policy and texts selection, click here.

☛ Cette chronique est aussi disponible en français [➦].

Translated by Chloé Sautter-Léger

The ways in which a community evolves differ based on norms, traditions and beliefs. The differences in integration for lesbian and gay groups is glaring across countries. In Mexico, integration difficulties are undeniable. With the influence of the Catholic Church, traditional sexual roles (i.e. men as purveyors and women confined to the domestic sphere) are an important part of Mexican society (Carillo, 1999). The Mexican Catholic Church considers homosexuality as something unacceptable and “wrong” (Beer and Cruz-Aceves, 2018; Bell, 2016; Froidevaux, 2018), even though the pope has declared that he does not condemn homosexuality (Radio-Canada, 2016). Taking on roles socially associated with the opposite sex can provoke discriminatory behaviours, since it is perceived as being contrary to societal values. In fact, until recently, the Catholic religion still perceived homosexuality to be a scourge which required addressing: “Just one month after the Mexican Supreme Court gave the green light for gay marriages, the Catholic Church has come out against same-sex unions by calling them ‘a public health problem’” (De Llano, 2015).

This article aims to distinguish the reality that certain members of the Mexican LGBT+ (Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Trans-Other)1 community experience, in contrast with the image of acceptance that Mexico is trying to project internationally. The text will examine the realities faced by gay and lesbian people concerning gay marriage, adoption, and everyday discrimination.

The overview presented here is based on a field study that took place in Mexico as part of a social science field research course at the University of Ottawa, during which we were able to meet various people involved in the fight for LGBT+ rights in Mexico. What our investigation showed was that while the LGBT+ community appears to be accepted and have equal rights on paper (in laws and political discourse), this is far from being the case in reality—both socially and institutionally. During our one-month stay in Mexico, we conducted semi-structured individual qualitative interviews in French, English, and Spanish. We met with men and women from different backgrounds with a wide variety of experiences—from LGBT+ activists to members of governmental institutions (including the UN), to individuals that identify as LGBT+. Due to the sensitivity of the subject, and to respect the anonymity of the participants, we will use only given names (and fictional names, for those who wanted to stay completely anonymous) in this article.

Love Each Other and Get Married

It is important to note that there are two prevalent perceptions in Mexico: the one projected internationally, in which laws and policies are created according to a philosophy of inclusion and respect; and the domestic perception, where these inclusive values are not necessarily honoured. This is the case, for instance, regarding same-sex marriage, which was legalized in Mexico in 2009. For instance, Roberto, a young Mexican part of the LGBT+ community, pointed out in his interview that people who want to get married are in fact often confronted with various obstacles, such as their state of residence refusing their union. Before getting married, they must undergo a long process (LaPresse, 2016). For example, Eduardo (fictional name) had to wait more than a year for the Supreme Court to overrule a refusal, finally allowing him to get married in his state of residence, and only after this process was he able to get married in his hometown.

In Mexico, there are 32 states, and only 11 legally accept gay marriage (Bell, 2016). According to Antonio, an LGBT+ activist, when two people of the same sex want to marry in a state where gay marriage is not legal, they have two options: they can either choose to get married in another city, or they can submit a waiver request to the Mexican Supreme Court for the decision of their home state to be overturned. This process can be long and tedious, however, and according to our interviews with members of the LGBT+ community, the process can be psychologically challenging for social and cultural reasons (Nakamura and Zea, 2013). In fact, people who decide to assert their sexuality in a way that goes against what is prescribed by the predominant Catholic religion can be subjected to multiple stressors, as found in their families, their communities or other spheres of their environment. These stressors are very real for individuals subjected to anti-gay world views, to domestic pressures, and to a dichotomy between belonging to the LGBT+ community on one hand, and their cultural and religious background on the other (Gilbert et al., 2016; Gray et al., 2016).

Clearly, there are true injustices that lie in having to face complex administrative procedures that heterosexual couples do not have to deal with. As said by Francesco, a student defending LGBT+ rights in Mexico City, “there is still a long road ahead before we can love each other like heterosexual people.”

A Family Affair

Procedures for gay adoption were legalized by Mexico City in 2009 (Pérez-Stadelmann, 2016; Saliba, 2016; Angulo Menassé et al., 2014). But realistically, it can be very difficult for same-sex couples who wish to adopt a child because of the notion of “natural family” (i.e. made up of a mother, a father, and X number of children)—something very established in Mexican mentalities. Antonio pointed out that because of this, homosexual couples can be subjected to many forms of discrimination which can jeopardize the adoption process.

For example, some people still believe today that homosexual men could be pedophiles (that is, be sexually attracted to children), and with this perspective, the adoption process for a couple of men is often made extra difficult. This prejudice was highlighted at the temporary exhibition “LGBT+: Identidad, amor y sexualidad” (LGBT+: Identity, love, and sexuality) at the Museum of Memory and Tolerance in Mexico City. One of the pieces in the exhibition posed the following question: “Is there a relationship between pedophilia and homosexuality?” The answer read, “There is no evidence to suggest that people of diverse sexualities are more likely than heterosexuals to abuse a minor” (Museum of Memory and Tolerance, 2018).

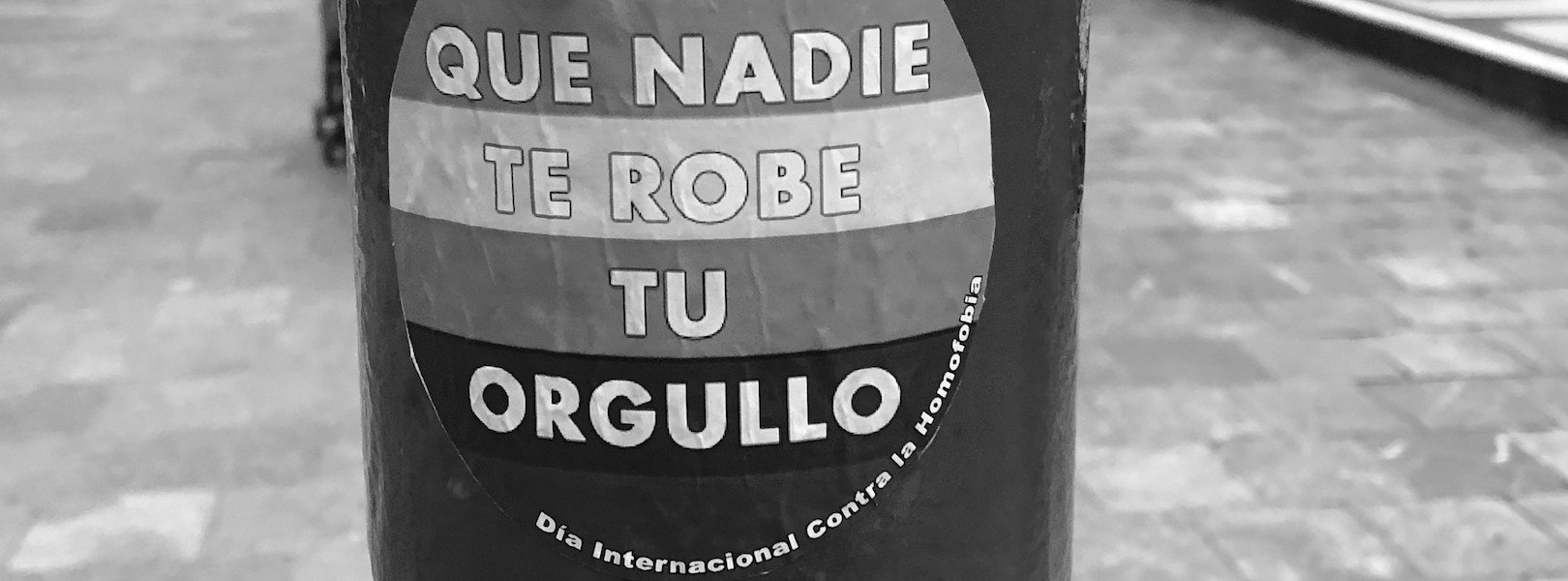

OFFICIAL POSTER FOR THE 2018 EXHIBITION, LGBT+: IDENTITY, LOVE, AND SEXUALITY AT THE MUSEUM OF MEMORY AND TOLERANCE IN MEXICO CITY

“THE CRIME IS NOT LOVE, IT’S PREJUDICE”: ONE OF THE POSTERS EXHIBITED AT THE MUSEUM OF MEMORY AND TOLERANCE IN MEXICO CITY

According to the people we met, this way of presenting things still suggests that there could be a link between homosexuality and pedophilia—in the sense that a lack of evidence does not reject the hypothesis. Such beliefs can strongly be influenced by the lack of sexual education within the Mexican population, as well as a lack of awareness concerning the diverse forms of sexuality (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018; Kàgesten et al., 2016). This can contribute to discriminatory behaviours and stereotypes about members of the LGBT+ community (Chandra-Mouli et al., 2018; Kàgesten et al., 2016), and can have a direct impact on adoption processes for homosexual couples, as adoption agencies may be less inclined to embark in an adoption process with a same-sex, especially male, couple.

Also, according to Agnès Chaudron, member of the Mexican embassy in Canada, and to Antonio, some Mexican communities project “thinking schemes” that suggest that the problem is not per se with children being raised by two same-sex individuals, but rather that it is “unfair” for a child not to grow up in a “natural family.” In fact, Antonio and Gabriella, both activists, point out that since 2016, there is a yearly march in Mexico called Marcha por la Familia, which aims to defend children’s right to grow up in a “natural” family (Bell, 2016 ; Echeverria-Garcia, 2016). For people like Katia, a young activist, this seemingly open way of thinking is actually a step backward rather than forward, because such a march leads to discrimination against the LGBT+ community (Bell, 2016; Echeverria-Garcia, 2016).

Accept Me as I Am

Most minority groups are victims of oppression, and the Mexican LGBT+ community is no exception. A 2016 study showed that in a sample of 912 people from the LGBT+ community, aged between 18 and 29, 67% were victims of bullying because of their sexual orientation during their academic curriculum (Baruch-Dominguez et al., 2016). Moreover, most of those who reported not being bullied said that it was probably due to the fact that their sexual orientation was not visible, i.e. they did not look like the stereotypical gay man or woman—a man displaying typically “female” traits, or traits “reserved” to women, or a woman displaying traits typically reserved to men (Baruch-Dominguez et al., 2016). In fact, a conversation with two members of the LGBT+ community, Katia and Andrea, revealed that their respective experiences had been entirely different because of their gender expression. Katia adopted a much more “masculine” look in university. According to her, the discrimination and bullying she had to face were potentially due to her more “masculine” style, often associated with a lesbian sexual orientation.

Discrimination can take many forms, and it is hard to draw a clear picture of the realities of the LGBT+ community in Mexico. The range of social practices and beliefs is extremely diverse. Mexico City is considered to be much more tolerant and open towards gay and lesbian communities than more rural states. This reality gives rise to migration of the young LGBT+ population out of rural regions towards the capital. For example, Francesco, a young student identifying as homosexual felt the need to leave his home town in the north of the country and moved to Mexico City, a place where he felt more accepted and free to be himself.

With the objective of improving the quality of life for sexual minorities, the CDHDF (Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Distrito Federal) began to register Human Rights violations committed against sexual minorities in 2006 (Commission de l’immigration et du statut de réfugié du Canada, 2011). This might give an impression of tolerance, but 11% of gay and lesbian people in Mexico City have received threats, were victims of extortion, or were detained by police because of their sexual orientation (Commission de l’immigration et du statut de réfugié du Canada, 2011). This suggests that there is a dark figure of crime with respect to Human Rights violations against sexual minorities in Mexico (i.e. unknown or unindexed crimes in the country’s official figures). That is, the way crime cases are handled when committed against a person of the LGBT+ community is not consistent with, or as effective as, the treatment of other cases. These cases are, indeed, often put aside or left unresolved (Mexique, n.d.; Red Nacional, 2010; La Prensa, 2011; Universogay, 2011, qtd. in Commission de l’immigration et du statut de réfugié du Canada, 2011). All this contributes considerably to the challenges lived by sexual minorities.

Furthermore, discrimination varies in relation to the sex, gender, and sexual orientation of the victim. Rosalba, Director general of human rights of the Supreme Court in Mexico of human rights at the Supreme Court of Mexico, told us that men identifying as homosexual are not perceived as “real men” and are as such often victims of verbal or physical violence. According to our conversations with Andrea, Francesco, Rosalba, and Katia, the violence experienced by homosexual women, is often more often of sexual nature. Andrea, Katia, and Rosalba all felt that lesbian women are potentially seen as a form of masculine sexual fantasy. Katia, for example, told us that when she walks hand in hand with her girlfriend in public, people often whistle at them or make sexual comments in reference to threesomes.

A research paper on homicides perpetrated between 1995 and 2008 showed that in that period, about 143 homophobic homicides were committed in Mexico City, of which 109 were against gay men, and only five were against lesbian women (Commission de l’immigration et du statut de réfugié du Canada, 2011). With a larger number of homicides committed against men, it could be instinctive to assume that homophobic violence is a bigger problem for men than for women.

However, as stated above, while there is more physical and verbal violence against men, women are much more often victims of sexual assault (i.e. sexual aggression).

This means that, while they do not undergo the same type of physical violence, homosexual women are far from being immune to violent forms of discrimination.

Still a Long Way to Go

Taking all this into account, the LGBT+ community in Mexico today is still subjected to discrimination, although it is possible to notice, to some degree, an evolution in the way of thinking. The authors of a study conducted in 2013 observed that mentalities are changing towards a more inclusive acceptance of the members of the lesbian and gay community of Mexico (Severson et al., 2013). Mexico has been dominated for years by norms inherited by the Catholic religion, which proscribes same-sex unions with the justification that they go against nature—that is, that the human body is not meant to mate with a person of the same sex (De Lano, 2015). Through a discussion with Enrique, who works for an NGO, we were able to understand that, although homophobic behaviours are still prevalent in Mexico, religious dogma is progressively abandoned by younger generations. According to him, younger people want to keep the memory of traditions, but are not necessarily practicing in the traditional sense. With this open-minded attitude, he told us, they keep their religious affiliation but try to adopt a critical stance on certain problematic dogmas, such as the ones that are overtly unfriendly towards the homosexual community.

The research we conducted during our month of field studies in Mexico helped us draw a clearer picture of the reality of homosexual Mexicans. As expressed by Rosalba, “The rules and values are there on paper, but they are not respected.” There is still a long way to go for Mexico to offer a safe and healthy environment for Mexicans of the gay and lesbian community. But the individuals we met were not afraid to affirm their rights and to make things happen. We are convinced that people like them will be able to increase awareness about the discriminatory realities faced by men and women identifying as homosexual.

1 Mexican terminology does not include the Q in the acronym.

To cite this article:

Ouellette, M-L. and Chénier-Ayotte, N. (2018, December 3). Identity, sexuality, and tolerance: an overview of sexual discrimination in Mexico. Les 3 sex*. https://les3sex.com/en/news/333/identity-sexuality-and-tolerance-an-overview-of-sexual-discrimination-in-mexico

Comments